By Tate Luckey

May is the start of a whirlwind of events in Louisville. It kicks things off with the Derby, all the students graduate about a week later, and then, while waiting for the next Waterfront Wednesday Act, locals are reminded of the suffocating pollen levels and record heat.

And yes, I mean record heat. Earth recorded its hottest year on record in 2024, in some places climbing as high as 1.5 degrees higher than average. That August brought Louisville its hottest day in 12 years – a scorching 102 degrees.

April’s rainfall led to record-high Ohio and Kentucky River cresting, flooding downtown streets, and (for the first time in my 22 years of life) eventually forcing the cancellation of Thunder Over Louisville. It devastated our state enough that our governor and entire congressional delegation are unified in urging President Trump for federal assistance.

It’s shocking, and according to modeling done by the World Weather Attribution, weather events like this are only projected to get more extreme over time.

Allergists note that a consistently warmer, wetter climate leads to a lengthier, more intense allergy season. This is especially true in Kentucky, with our high populations of pollinating juniper, maple, and elm trees. The Asthma and Allergy Foundation’s 2025 Allergy Capital Report ranked Louisville as the 69th worst city to live in if you have allergies, partly due to our increased medicine use.

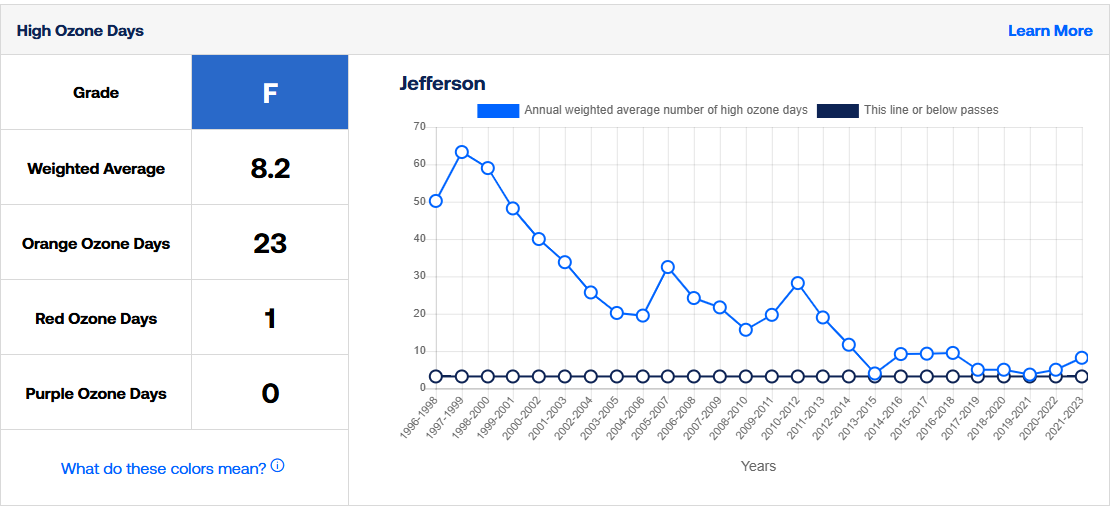

A snapshot from part of the American Lung Association’s 2025 “State of the Air” report card for Jefferson County. Though it’s been a downward trend, Louisville has an average of 8 days of unhealthy air a year.

It should surprise no one, then, that the American Lung Association gave the Jefferson County metro area air an “F” grade, meaning tens of thousands are at risk for developing conditions like COPD, asthma, and lung cancer. Louisvillians spend more than a week every year breathing unhealthy air. “Unhealthy days” for ozone pollution here average eight per year— an increase from the five-day average reported last year.

If you walk around downtown, it’s not hard to see why. The high car usage, parking lots, and drab buildings don’t exactly scream “breathe me, the air is clean!”

In a conversation I had with Sean Willis, a Louisville native and research technologist at the Urban Design Studio, he estimated that 21% of Downtown Louisville is surface parking lots.

That stat alone is why he and other researchers transformed one plot of land–Founders Square–to make a different impact.

Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg was joined by U of L President Gerry Bradley and students from the J. Graham Brown School at the unveiling. TreesLouisville was on site throughout the day, handing out various young native trees to plant. (photo courtesy // U of L News)

Phase I is complete

Researchers at the Urban Design Studio at U of L’s Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute have just completed Phase I of the Trager Microforest, a ⅔ acre greenspace built over Founders Square. The gaudy x-shaped path has been intentionally redesigned with a new circular, bench-lined concrete ring that contains approximately 150 native trees, 250 small shrubs, and ground plants to create a dense natural tree canopy. Multiple data collecting devices, including wet bulb monitors and a central station referred to as “the Campbell,” are integrated around the space.

Willis called the microforest the “perfect storm of low-cost, high-effect intervention”.

The pitch was simple: how can this small, high foot traffic lot be turned into something uniquely functional and scientific?

Founders Square runs alongside the second most-used TARC bus line in the city and is positioned right in the heart of downtown. While other paved lots may cost millions to buy and redevelop, Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg and the city worked with the Envirome Institute to get the 30-year lease at the Square for around a dollar.

At that point, the Trager family matched up to one million dollars in total donations, which was concentrated toward the greenery and construction.

Phase 2 is set to include more community-oriented features for plant protection and safety, including fencing to protect the trees and a small, public community space in the Southwestern corner.

“At the end of the day, [we had to] make a decision between having it be safe versus accessible, and [in some cases] we leaned more into accessibility,” Willis described.

This decision-making even impacted the types of trees planted. They could’ve planted evergreens, since those grow and contribute the most shade and cooling, but that creates a visual barrier. The middle is intentionally left more open, both for visibility and so it’s not considered “hostile architecture”.

The Northeast Entrance of the Trager Microforest and the initial stages of planting back in November 2024. (photo courtesy // Sean Willis, U of L Urban Design Studio)

But how does it work?

The multilevel canopy develops faster when native trees are planted in a tighter space. This is called the Miyawaki method, developed by Japanese botanist and plant ecologist Akira Miyawaki in the 1970s. As the trees mature and compete for resources, researchers at the Envirome Institute plan to collect data over the next 20 years to track all aspects of how the microforest is impacting residents’ health. This includes tracking their heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and even notes on their behavior within the newly built forest.

It’s not exactly a new idea; in 2024, the conservation group SUGi completed similar projects in high-density places like Roosevelt Island in New York. This past March, West Los Angeles College held a planting day for their new campus microforest. The effects microforests have in their immediate areas have been promising, increasing biodiversity and helping cool the area, which is much needed downtown. Urban city temperatures can read as high as 10°F hotter than the suburbs, due to the intensity of heat-absorbing materials in the downtown districts and the relative sparseness of tree canopy, which provides evaporative cooling and shading. A 2022 Urban Tree Canopy study found that Louisville’s total tree coverage is at 39%, a steady 1% gain compared to 2012.

Researchers in India claim that microforests aren’t exactly the best way to reduce a city’s carbon footprint, especially if hastily done, but ultimately, Willis and the team are excited by the momentum this project provides. The Institute is currently fundraising for the completion of Phase 2, and hopes that this microforest model can be an example not just for Louisville but other similarly sized U.S. metros.

As he told me, “There’s a reason people seek the shade.”

He’s already begun seeing a change in how people use the space: government employees on their smoke breaks are instead slowly turning into birders, lingering just a little bit longer to take in the promising lush greenery.

Tate Luckey is a recent graduate from the University of Louisville and the former Editor-in-Chief of the Louisville Cardinal, holding the position from 2022 to 2024. Visit Tate’s Substack to find more of his work.