By Sammie Hill–

Enticed by the title and the fact that Cheryl Strayed wrote the introduction, I decided to purchase Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere on iTunes and read it on my phone, since both Barnes and Nobles in Louisville didn’t have it in stock.

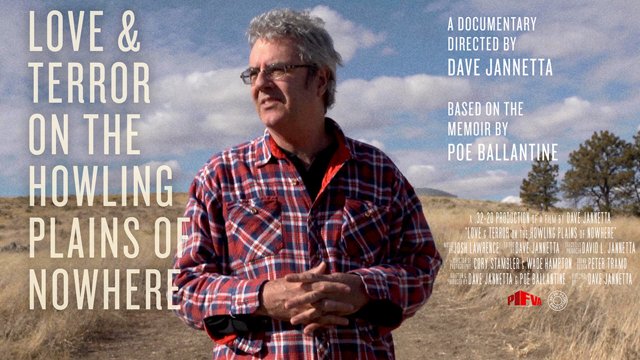

Love and Terror on the Howling Plains of Nowhere, advertised as a memoir entwined with a true crime story, chronicles the author’s life in small-town Nebraska, where a startling and mysterious death prompts Ballantine to launch an investigation of his own into the case.

Though he has settled down with a wife and child in the small town of Chadron, Ballantine recounts his earlier days spent as a restless drifter, a failed writer, a bright but unmotivated student and a suicidal vagabond. The now settled down Ballantine, intrigued by the death of his community member and in need of a topic for his new book, strives to solve the case himself while reflecting on the experiences of his own life.

I finished the book in one day. I didn’t want to stop reading it for two reasons: because I wanted so badly to like it, and because I wanted to see the case solved. However, I finished the book with a sense of disappointment.

Although at times I felt enchanted by Ballantine’s language, I also found myself put off by his egocentricity and tendency to cycle through the same repetitive information. I kept hoping his book would amount to something, that I would feel satisfied after flipping through 656 pages on my phone, that the book would move me and blow my mind and break my heart. But it didn’t.

Ballantine decided to write this book before he even began investigating the case. He then invested time and effort into his amateur investigation, and he wanted to sell a book as a result.

However, there just wasn’t enough about the case to generate an entire book, and it seems as though Ballantine fused the genres of memoir and true crime because neither one would be substantial enough to stand on its own. Together, however, they just didn’t make a lot of sense, and left me wondering what his purpose was in writing the book at all.

Ballantine’s stories of his past, while diverse and intriguing, didn’t seem to tell me much about him. He tell us he was restless; he tells us he was suicidal; he tells us he’s lived in a thousand different places, moving around every few months because of self-loathing and an unwillingness to settle down. But for some reason, I still never got the sense that he was writing with true vulnerability, with raw honesty. He claims throughout the book that people found him difficult to trust, and I can see why.

Though he claims to be self-loathing, his stories always seem to paint him in a positive light. For example, one day he takes his son to the park, and his wife—depicted as cold, confused and incomplete throughout the book—insists on leaving after 20 minutes, but Ballantine refuses, and he and his son stay while she leaves “without a word.” His son can’t sleep one night because of a cough, so Ballantine decides to give the five year old a mixture of Bailey’s Irish Cream and ibuprofen; when his wife objects, he portrays her as rash and over-dramatic for being concerned about this home remedy, while he smugly points out that his son woke up feeling uncharacteristically refreshed and well-rested the next day.

Meanwhile, for only about the last half of the book, Ballantine interjects information about the case he is investigating. The case, morbidly fascinating due to the circumstances of the man’s death, kept me reading after I had tired of Ballantine’s thinly veiled endeavor to convince the audience of his strong character.

However, Ballantine’s inclusion of the case in his book is exploitative. He investigated the death of a virtual stranger, revealed intimate details of the man’s life and gruesome details of his death, and published a book about it against the wishes of the family of the deceased.

Ballantine challenges the family’s conclusions about the man’s death, suggesting that it was a murder rather than a suicide. He cycles through the same evidence and same theories that serve only to re-open the family’s wounds and to sell the book. To give favor to his own theory, Ballantine belittles the deceased man’s struggle with depression—in fact, he trivializes the concept of mental disorders in general.

Ballantine’s book, and the documentary based on it, continues to bring up this tragedy, prohibiting the family from attaining a sense of closure. Ballantine criticizes the family for not wanting to find out the truth, while the family—who actually knew and loved the deceased man, unlike Ballantine—insists that they know all there is to know, and just wants to put the tragedy behind them.

They want their loved one to be remembered for his life instead of for a sensationalized story of his death, told by someone who never even knew him.

After I had gotten into the book a little bit, I considered including it in my “Best books to read in college” column. Ballantine has talent as a writer, some of his experiences would enthrall college students, and his autistic son Tom is cool as hell.

However, after I reached the inadequate ending and read online about Ballantine’s decision to pursue the case and publish the book against the family’s wishes, telling the story in a way that interferes with their sense of closure, I abandoned that idea.

Yes, Ballantine has a right to tell the story of the man’s death, but if you ask me—and the family—it is not his story to tell.

The book as a whole almost seems purposeless except to convince Ballantine of his own insight and importance. Thus, while he did impress me as a writer, I would not recommend this book to others out of respect for the family of the deceased, and because of the overwhelming sense of disappointment with which it ultimately left me.

Photo courtesy of vimeo.com

For those interested, this comment thread includes a discussion among members of the deceased man’s family and Ballantine himself: http://hawthornebooks.com/blog/article/poe-ballantine-on-the-documentary-love-terror-on-the-howling-plains-of-nowh