Go peruse the shelves at any local textbook store and you’re likely to find a number of professors moonlighting as authors. Those textbooks are usually used in the authors’ classes. Why? It depends on who you ask.

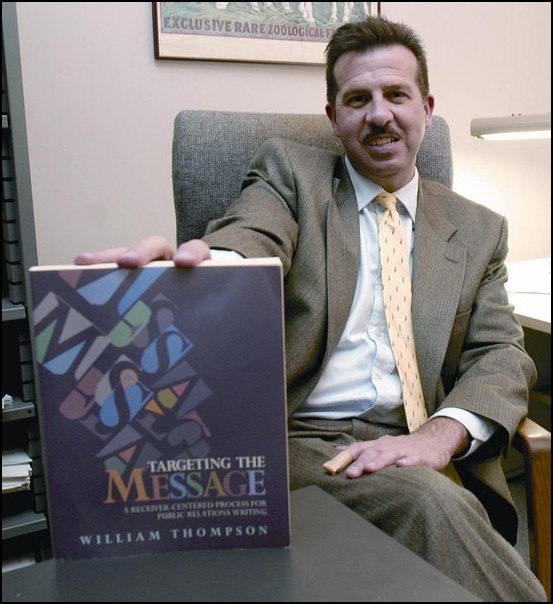

Communication professor William Thompson uses his book, “Targeting the Message,” in one of his public relations classes. His book fulfills what he called the “niche market” of P.R. writing.

Unsatisfied with what was on the market already, Thompson wrote his own book. He said it was pointless to have students pay $60 for a book they wouldn’t use because it didn’t reflect what he thought was important.

That reasoning is motivation for many professors to write their own texts, he said, as opposed to fame, fortune or spite, as students commonly believe.

Thompson insisted that, while journal articles are more prestigious, good textbooks are just as noteworthy.

“It’s a very creative enterprise,” he said.

For the 18 months that Thompson was writing his book, he had to think about his subject in a different way, a way he described as very systematic. Now his classes are structured so the text supplements the lecture.

“I think it’s made me a better teacher,” he said.

Thompson was frank about the downsides, though. “It’s so terribly self-referential,” he said. “You quote yourself a lot.”

However, since his book’s publishing, Thompson has changed his mind about some aspects of public relations. He said active scholars should occasionally shift positions due to additional research and new developments, even though it might appear to be a contradiction.

Thompson is adamant about being up front with students and admitting to – and explaining – changing viewpoints.

Some students feel they’ve been swindled by professors trying to make a buck at their expense, but according to Thompson, the textbook publishing biz isn’t very lucrative, especially at the University of Louisville.

According to Dean Blaine Hudson, the College of Arts and Sciences enacted a policy in 1998 stating professors can use their own works as required reading but may not receive royalties.

According to the statutes, professors in A&S must donate the royalties from their textbooks back to the university or reimburse the students the royalty amount.

When professors do earn royalties it is usually only 10-15 percent of the wholesale price, and wholesale is usually half of the bookstore cost.

Professors do not earn royalties on used books, either. Thompson agreed that is the reason for “revised” editions.

The lack of monetary gain raises additional questions for some students. For example, last semester Dr. Robert Kebric required two of his textbooks, in addition to the standard textbook, to be purchased for History 101. When asked to be interviewed on the subject, Kebric declined via e-mail because the topic “has too much room for misinterpretation.”

What is being misinterpreted is his reason for requiring the additional textbooks, which, according to students in the class last semester, cost $45 each (new) and were of limited use.

“We didn’t use them that much,” said sophomore Jackie Lile, who was in Kebric’s class. She said he lectured using the information from his books, making the information redundant. However, students did find the information they needed for exams in the books.

Lile said she assumed Kebric wanted the royalties. When informed that he couldn’t receive royalties, she wondered why they were necessary.

For some professors, the opportunity to research is the reason they strove to obtain their educational status, and the textbooks bearing their names serve as proof of that expertise.