Bert Harris knows the dichotomy of Vietnam. The theater professor made films for the army about Vietnam. He admits it was propaganda.

One of the films he made contrasts the need for growth in Vietnam and the savagery of war. The film focuses on the building of roads. Harris saw it as a positive development, a needed improvement of infrastructure, but he knew that such roads would help the military move heavy equipment.

There was more for Harris. A certain anarchy, a lack of rules existed within Vietnam. “A unit could be out in the middle of the jungle, in the middle of nowhere and have steaks flown in. It was a weird luxury and a strange existence. The person doing your laundry could be giving you a bomb the next day.”

All this came together in one piece of art work in 1979. Its name was “Apocalypse Now.””There’s some nice movies set in Vietnam; some are a disaster,” Harris said. “It is the fact that this movie gets at the insanity of Vietnam in a tangible and real way (that makes it a great film).”

Humanities professor Tom Byers, who saw the premiere of “Apocalypse Now” in 1979 in New York City, agrees: ñSome people would say that you can’t uses simple realism to tell the story of Vietnam. It’s a wild, scary movie that feels like it’s made by people battling their own demons. That’s what Vietnam ended up like.”

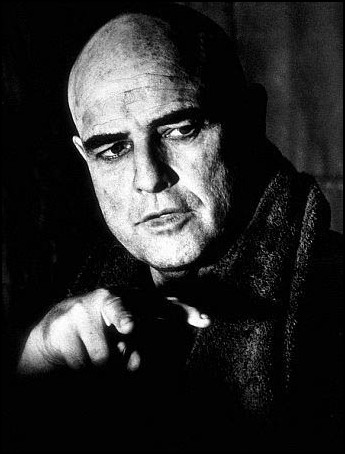

“Apocalypse Now” tells the story of a man sent on a mission to kill a madman, Col. Walter Kurtz (played by Marlon Brando). He resides deep in the jungle, and kills Vietcong troops and spies without mercy, without trial, without order. The Army Cap. Willard (played by Martin Sheen) must travel through Vietnam with a band of young men, up the river to kill Kurtz. The men are young and represent different areas of the country (one is even played by a young Lawrence Fishburne).

The film draws a variety of things from the 19th century work, “The Heart of Darkness,” by Joseph Conrad. In that work, an army captain travels up a river in the Congo to kill a British renegade soldier (also named Kurtz).

“In the ‘Heart of Darkness,’ Conrad saw the whole hypocracy of colonialism,î Humanities professor Michael Johmann said. “He spent a lot of time dealing with issues of the dark and the light. The natives, who were considered pagans because they did not believe in Jesus and were not developed, spent most of their time in the dark. While the white is supposed to be good. It’s supposed to be the Europeans. But the white becomes empty and evil. The thing the Europeans are looking for is ivory, which becomes the symbol for white.”

In “Apocalypse Now,” the armyÍs reason for killing Kurtz is because the man has clearly reached the threshold of what can be tolerated. But Willard sees the hipocracy in the army’s message, as he remarks: “Charging someone with murder out here was like handing out a speeding ticket at the Indy 500.”

The films shows the acceptance of madness. “It says something about the inherent madness, especially in war,” Johmann said. “That we can be absolute savages by the rules. We donÍt recognize in war our own hipocracy. Kurtz is a far more honest character. The honesty is the horror he talks about at the end of the film that we’re capable of.”

Willard runs across a variety of characters and witnesses various things to demonstrate this fact. One of the characters he runs across is a captain (played by Robert Duvalle).As Willard and his men fly into where their boat needs to be dropped, the captain drops bombs on the Vietnamese and talks about how the tide is for surfing. ñI love the smell of napalm in the morning, it smells like victory,î he says as they napalm the enemy.

The captain’s dichotomy comes across even more when they land on the ground. In the scene he comes over to a wounded Vietnamese man and remarks on how much courage the man has to hold his guts in, but then finds out a famous surfer is in the vicinity and loses his attention for the Vietnamese man.

“You never catch the guy acting,” Harris said of Duvalle. “It’s an outrageous character and somehow he makes you believe it. Everything he does is done with honesty and truth.”

Willard then travels up the river in his gun boat and encounters various things along the way until they reach the camp of Kurtz, who remain secluded and indifferent to everyone. The men waterski and smoke pot.

“The drug use is a very real element,” Johmann said. “Soldiers who fought in Vietnam were much young, a pool of drifters that came from the urban inner city, minorities from malnourished areas. They were poorly trained and poorly educated. Drug use in the movie followed the times.”

Harris said that the camp of Kurtz was the major disappointment in the film for him. At the point they reach the camp is the point he stops watching. It’s the one part of the movie that does not work for Harris.

“To me, it’s mundane and small,” Harris said. “It feels like a callosal letdown in my view.”

Dennis Hopper, who plays a journalist in some half baked fashion, adds to the problems. “It was a typical Dennis Hopper performance,” Harris said. “He’s such an odd and grotesque type. I donÍt believe it works. That character doesnÍt bear any resemblance to anyone I ran across in Vietnam. I’m not saying that this type of person never existed in Vietnam. It was just not part of my experience.”

For others, Kurtz, played by Brando, provides the major problem in the camp scene.”I think Kurtz is better heard than seen,” Byers said. “In ‘The Heart of Darkness,’ Kurtz is mainly a voice. ItÍs better imaging him. He’s scarier if you imagine him for yourself.”

For Harris, Brando is Brando, the great method actor: “Brando brings a presence to the role. He puts such a stamp on every role he plays. It’s hard to imagine anyone else playing Kurtz.”

Despite the poor series of scenes at the end, the movie still was very important, because Vietnam was very important, a watermark in our civilization, says Byers: “Vietnam was a profoundly shaping event for the consciousness of people born in 1940 and afterwards. It’s an event that we have to have movies about. Some of them are remarkable. Some are awful. ‘Rambo II’ repaints us as the underdogs against the imperial power. It was sort of this whole American business about shooting and running and the British simply werenÍt up for the fight. We were like the British in Vietnam and they used the guerrilla tactics against us. It (movies like ‘Apocalypse Now’) made us the bad guy in our own myths.”